Back in Business

Tortoise, Bill Frisell, Philipp Gropper's Philm, Kaufmann/Dimitriadis/Thieke, and Nicolas Collins & Birgit Ulher

After yet another disturbing week in the US, which has left me angered, depressed, and frustrated by the inability to do much about the dire state of my birthplace I’ve managed to slough off depression and to focus on creativity that functions like resistance to the cookie-cutter uniformity and acquiescence the fascist regime demands. If you’re reading this week’s newsletter via email it’s possible that some portion of the recommended shows list has been cut off, but you can easily access all of it by clicking the banner, which will take you to the web-based iteration.

A Tortoise Retrenchment

I’m not boasting when I say that I’ve been listening to Tortoise since the very beginning. I caught their very first performance in 1992, when they were still called Mosquito, and I had been seeing its members play in bands like Eleventh Dream Day, Precious Wax Drippings, Bastro, and the Tar Babies for years earlier. Last November Tortoise released Touch, their first new album in nine years, and their first album on a label other than Thrill Jockey, the imprint owned by Bettina Richards that was so crucial to documenting the Chicago underground rock scene in the 90s. The record was issued by International Anthem, another Chicago-bred label that’s released a slew of albums by the band’s guitarist Jeff Parker, and which certainly seems to define a certain segment of Chicago music now the way Thrill Jockey did back in the day.

The recording took years to make, understandable given that the group’s members are now located in Los Angeles and Portland, in addition to Chicago. The musicians are older but still active in many different projects, so while Tortoise might be the most celebrated group most of them have worked with, it no longer feels like their identity some 34 years after it all began. I think the last Tortoise album that genuinely rearranged my thinking was Standards, which came out in 2001. Touch is only the fourth album they’ve made since then, and while I have enjoyed all of the releases in between, there’s something about this one that feels different.

There’s something raw and almost brutal about its sound, with a kind patched together quality that might be explained by its extended incubation time and the fact that the quintet used three different studios to make it. But that quality feels fresh in this case, perhaps reflecting a quilt-like methodology on one hand and weird Lee “Scratch” Perry-style production techniques that seem to embrace a sense of sonic dislocation, on the other. The opening seconds of “Vexations,” which begins the record, sound wobbly, as if recorded on crinkled tape, with a meandering, processed guitar tone that reminds me of “Swung From the Gutters”—a classic jam from the 1998 album TNT—before a chugging, chunk groove melding the band’s trademark post-Morricone twang with overdriven guitars and queasy keyboards enters the fold. It sounds like a sinister, beaten down relative of “Telstar.” But like most of the songs on Touch, its deliciously multipartite, shifting into new sections or complexions, with a ferocious Jeff Parker solo and everything pushing into the red.

One of my favorite tunes is “Works and Days,” a mid-tempo jam rooted in electronics with the kind of cinematic melody, fuzzed guitar, and elegant vibraphone that feels characteristic of the band’s sound over the long haul, but the way these elements are assembled provides a compelling three-dimensional quality, with discrete layers giving the arrangement a thrilling dynamism, enhanced both by squelchy electronic tones and field recordings made by Portland-based producer Tucker Martine. The collision of electronic grooves with guitar, bass, and drums has long defined Tortoise, and it’s carried forward in new ways by tracks like “Elka,” which veers out of twitchy electro with an arcing melody underlined by the strings of Marta Sofia Honer and Skip VonKuske, or “Axial Seamount,” where live electronics thread a taut electro groove that could’ve come from an early Air record. I’ve always been flummoxed by people who call Tortoise a jazz group, a misguided categorization I’ve also seen applied to Touch, but one of my favorite tracks certainly transmits the complexion of jazz through Parker’s sophisticated harmony on the album’s first single “Organesson,” where so many trademarks come together, its tightly-coiled rhythms piercing the wide-open vistas of Parker’s chords, with the various layers arriving like overlaid transparencies. Check it out below. Rather than privileging seamlessness, the best moments on Touch celebrate those stitches, and while we might not be able to expect bald innovation any longer, Tortoise finds fresh recombinations. The group plays a sold out show at the Großer Sendesaal rbb on Thursday January 29. Parker is sitting out this tour, so the guitar role is taken by James Elkington, a remarkably versatile player who’s become a key fixture in Chicago through his membership in Eleventh Dream Day and Brokeback, the band of Tortoise bassist Douglas McCombs. He’s also been an auxiliary member of Tortoise when it’s embarked on various retrospective projects.

Bill Frisell’s Bounty of Possibilities

On his forthcoming new album In My Dreams (Blue Note), out February 27, guitarist Bill Frisell continues to refine and tweak the various elements that have comprised his oeuvre for many years. From his emergence in the early 1980s well into the current century he frequently overhauled his aesthetic thrust without ever abandoning an essential, melody-rich core rooted in Americana. Over time he teased out and honed various areas of inquiry, some discreet, some overlapping. The presence of twang might emerge on a record devoted to country music or within a post-modern spasm during a period when he was closely affiliated with John Zorn. But for a while now Frisell has settled into those various modes, content to toggle between an assortment of long-term projects that feel like working bands that just happen to take an extended hiatus on a regular basis.

He plays in Berlin on Monday, February 2 at Zig-Zag Jazz Club, leading a trio with drummer Rudy Royston, who appears on the new album, and bassist Luke Bergman, who doesn’t. In My Dreams brings Frisell together with five long-time collaborators, all string players apart from Royston. Double bassist Thomas Morgan has worked with the guitarist often in recent years, and in fact he’s the regular bassist in Frisell’s trio. Cellist Hank Roberts, violinist Jenny Scheinman, and violist Eyvind Kang—who just played an extraordinary duo concert with vocalist Jessika Kenney at KM28 on January 17—have all played with him at various junctures in different ensembles, including the 2005 album Richter 858 (Songlines), which features all three. The strings in the new sextet move easily between playing plangent yet leisurely section parts, operating as a compact orchestra for Frisell’s ever-lyric solos, and shaping unobtrusive counterpoint to inject friction or radiant melodic responses. Of course, they all get to solo here and there, too. The strings never feel perfunctory or tacked on, imbuing every arrangement with genuine personality and rich graininess. Below you can check out the title track, a muscular ballad that accrues intensity and depth as it proceeds, with the lilting string part turning up the heat with each chorus, Royston hitting harder, and the guitarist maintaining equanimity through turbulence.

The core of the album is taken from three live performances in Brooklyn, Denver, and New Haven across 2025, but substantial additional recording was done in the studio with Frisell’s long-time producer Lee Townsend. The recording is gorgeous and full of subtle detail, such as the way Frisell’s crystalline articulation of the brilliant melody from Billy Strayhorn’s “Isfahan” carries forth with only Morgan and Royston for nearly three minutes before the strings emerge, which admirably only make spare commentary on a tune that’s famous thanks to the lush arrangement on the original Ellington version from The Far East Suite, with one of the greatest late-career solos of Johnny Hodges. “Curtis (a year and a day)” is a feature for Kang, whose phrasing and tone betrays his ardor and knowledge for Persian and Indian traditions, but it’s masterfully situated within the feeling of the tune, which is Frisell’s and marked by a dusky melancholy. It’s nothing short of ravishing. Beauty emerges in a different way on a brief stroll through the evergreen Stephen Foster song “Hard Times,” with a largely composed arrangement, its edges kissed by typically gauzy Frisell ornamentation. The music might not surprise you on the surface, but the rigor, tenderness, sense of space, and rapport of the players delivers something more profound and empathic.

Philipp Gropper’s Philm, Hiding in Plain Sight

It’s been almost seven years since Berlin tenor saxophonist Philipp Gropper has released new music from his long-running group Philm, but that doesn’t mean they haven’t been working and developing new material. In fact, tomorrow the group will release two albums of new work, each titled for the year they were made: 2024 and 2025, both unexpectedly issued by the Berlin punk imprint Bretford. Ably supported by double bassist Robert Landferman, keyboardist Elias Stemeseder, and new drummer Leif Berger (who’s replaced Oli Steidle), the quartet presents two related sides of its off-kilter post-bop, an intensely jagged, polyrhythmic assault of seemingly incongruous lines.

I’m not exactly sure why it took so long for new music to get released, but there’s no question that the complexity of the material required a lot of rehearsing, especially with a new group member. But Berger has proven adept at marshalling such mutli-layered, herky-jerk grooves in the past, and here he takes the lessons of Jim Black into the stratosphere. 2024 is the more extroverted and jarring of the two albums. The band is incredibly impressive at navigating the material, forging a kind of rhythmic jujitsu that smashes freebop with the most angular hip-hop breaks imaginable. Stemeseder’s insistent, stabbing piano riff on “ray” coupled with Berger’s lurching beat evokes the lopsided elegance of Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s classic “Shimmy Shimmy Ya,” although I doubt it’s an intentional reference. The track opens up, carving out a labyrinthine path for Gropper’s probing tenor, with Landfermann’s typically agile virtuosity holding it all together. Check it out below.

There are times when the rhythmic complexity can feel a bit too fussy, with the musicians more interested in nailing difficult passages than creating something cogent, but luckily that’s not the case most of the time. A few weeks ago I mentioned how Stemeseder’s gigantic keyboard arsenal seems to occasionally overwhelm him, leaving him frozen by too many choices, but the way he toggles between piano and synthesizer in Philm captures his versatility at its best, a constant dance between rhythmic ferocity, eerie ambience, and harmonic framing. In fact, he and Landfermann give Gropper and Berger significant leeway to push against the grain, and if we can parse the way the various grooves fit together in spite of themselves, we can focus on individual lines, especially the leader’s liquid tenor, which is just as likely to mimic the shape-changing properties of mercury as it is to reinforce the elaborate rhythmic armature.

The music captured on 2025 is less frenetic even if the same polyrhythmic rigor remains. The group achieves a stunning cohesion on its predecessor, and here it seems like the quartet has less to prove, although it’s more likely than Gropper’s newer tunes simply called for less intensity. The comparative chill allows the listener to break things down more easily, and while the ballad-feel of a track like the pensive opener “what to?” sounds more identifiably like “jazz” than anything on 2024, with Gropper’s sculptural solo and the post-Bill Evans harmonies of Stemeseder unfolding patiently, the m.o. hasn’t really changed. You can sense that slowed-down vibe on “no words 1,” below, which is akin to a DJ Screw remix of a track from the earlier recording, but hearing the tight connection between Landfermann’s muscular, fat-toned and tightly coiled lined and Berger’s lurching groove—suggesting a tap dancer falling down a flight of stairs—proves they’re not simply reducing the tempo. The quartet will celebrate the release of the albums with a performance at 90mil on Tuesday, January 27. Lucy Zhao, a pipa player from China who’s based in Berlin, plays an opening set.

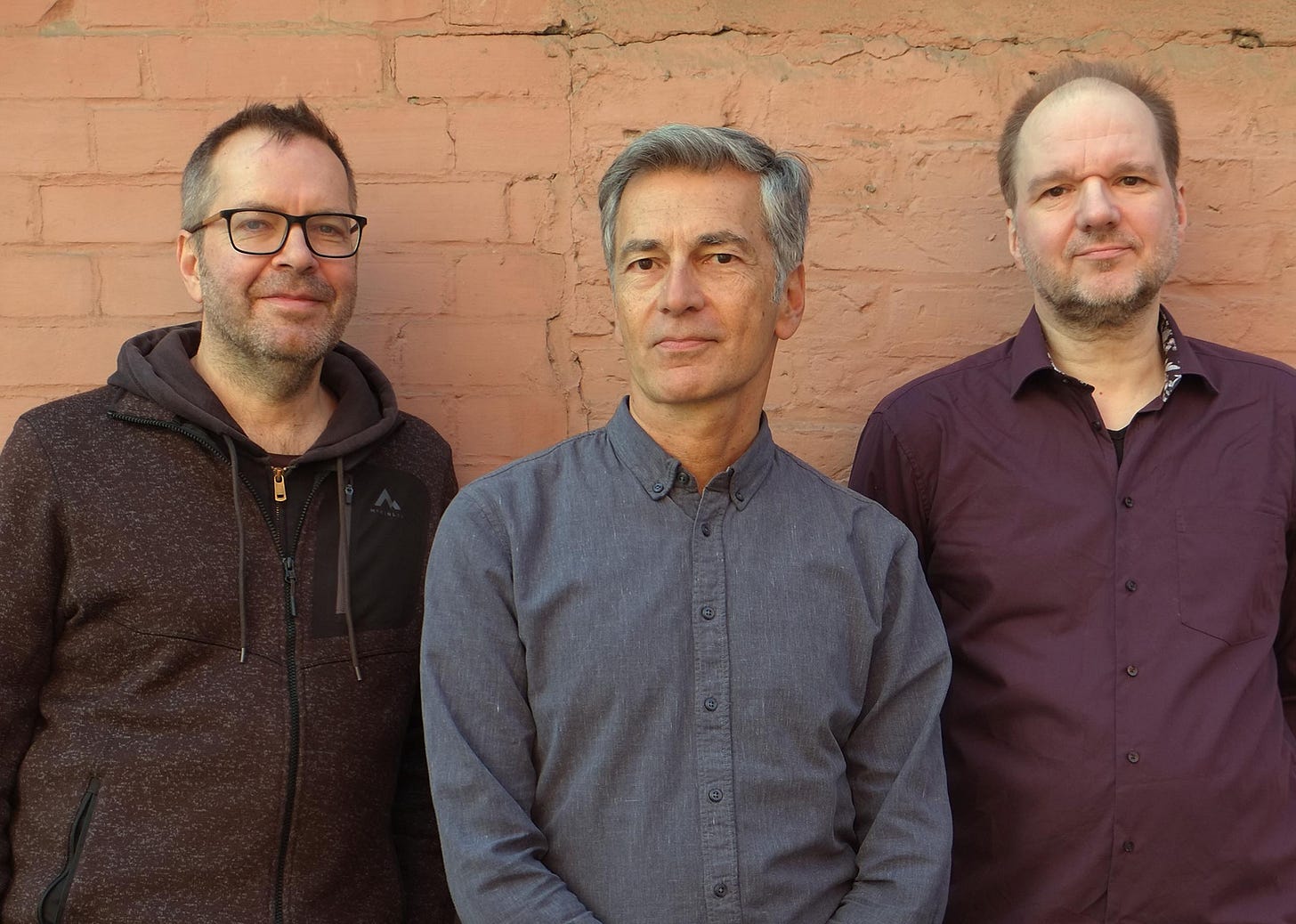

Achim Kaufmann, Yorgos Dimitriadis, and Michael Thieke Straddle Divides

Last December I wrote about Diaphanies (Granny), a recording of exquisite detail and anticipatory clairvoyance by clarinetist Michael Thieke and percussionist Yorgos Dimitriadis. Their blend of reduced, gestural sound represents so-called lowercase improv at its best, where quietude and patience are assets rather than gimmicks. But the album sometimes busts out of this sonic neighborhood with more forceful, full-bodied utterances in which their instruments aren’t camouflaged by extended techniques or pruned down to the smallest utterances. Both musicians have real jazz roots, and some of the action betrays that grounding. On the other hand I’ve always identified pianist Achim Kaufmann as a jazz-rooted musician who happens to have such a strong command of prepared piano and extended technique that his excursions into more abstract, restrained activity can feel like a logical outgrowth of his more conventional playing.

All three musicians have worked together in various combinations in the past—beyond the Thieke-Dimitriadis album from December, the drummer released a terrific album with Kaufmann called Nowhere One Goes (Jazzwerkstatt) in 2024 where the action toggles between heady free jazz and extended explorations of abraded texture and rhythmic confusion. Late in December the trio released Hiss and Whirr (Wide Ear), its first recording together, which naturally straddles these various divides. On the title track Kaufmann’s preparations transform his piano into a kind of muted set of chimes which interlock nicely with the spacious, at times gagaku-like rumble of Dimitriadis, as Thieke’s gently slaloming, brittle split-tones unfold in the distance, as a kind of connective tissue. I couldn’t even say what Kaufmann is doing deep in the recesses of “of fragments flowering.” In the foreground Thieke unfurls sputtering, highly rhythmic patterns built from unpitched breaths while Dimitriadis generates a delicate clatter that surges and ebbs, occasionally cut with electronic squiggles. That leaves softly ringing tones that could be electronically mediated; sustained, washed-out ringing of unclear provenance, but I’m betting it’s the pianist. Below you can hear the piece “an epoch of rain,” where the sounds aren’t so elusive: Dimitriadis creates a splatter of cymbal play, Thieke blows high-pitched sustained tones, and Kaufmann unleashes pointillistic prepared piano lines, building in tension through volume and volubility. As the album proceeds Kaufmann’s pure piano tones become more prevalent, but the sharp attention to detail, the quicksilver responsiveness, and the command of timbre is dazzling no matter how they make those sounds. The trio celebrates the release of the album with a performance at Sowieso on Wednesday, January 28.

Nicolas Collins & Birgit Ulher—Not Exactly a Trumpet Duo

When the experimental electronic musician Mark Trayle let his friend Nicolas Collins know about a job opening in the sound department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago back in 1999 he quipped, “You could play trombone with the AACM.” Collins relayed the witty communication in his terrific memoir Semi Conducting, which I wrote about when it was published last year. Collins ended up landing the job, which he held for more than two decades, but the joke referred to the fact that he couldn’t play trombone at all despite being closely affiliated with the instrument, which he used as a sound controller and shaper. His “trombone-propelled electronics” was one of the most important tools in his vast sonic repertoire.

On Wednesday, January 28 at KM28 Collins will take the stage with the veteran experimental trumpeter Birgit Ulher, celebrating the release of their new duo album Spark Gap (Relative Pitch)—Hanno Leichtmann will also perform a solo set. Both Collins and Ulher will hold trumpets to their lips, but as with “trombone-propelled electronics,” the sounds Collins produces won’t be brassy in the slightest. In fact, despite the look, he won’t actually be playing the same instrument as Ulher. His current tool is what he dubs “!trumpet,” which also uses a horn of the same name and design as a new sound controller and shaper, a self-contained amplifier made with a self-designed computer program that simulates the hacked circuits Collins spent years manipulating with analog technology. The strength of his breaths is a controlling device thanks to a pressure sensor built into the mouthpiece, while additional sensors in the horn’s three valves offer another set of controls read by an Arduino and fed into a laptop running Max/MSP. Collins can toggle his output between a speaker built-in to the bell of the trumpet or to the PA system, while an external plunger mute is loaded with additional switches. His set-up contains a mixture of the hacked circuits and sonic artifacts inspired by some of his favorite improvisers, including Ulher. The entire device is more sophisticated and can do more than what’s suggested by this thumbnail sketch, as the new recording makes plain.

Ulher is a seasoned improviser who has rarely deployed conventional language for trumpet. On the new recording she deploys various objects, speakers, and radio to alter and mutate brassy puckers, unpitched breaths, and other extended techniques. Although the timbre of Collins’ !trumpet certainly distinguishes it from Ulher’s acoustic utterances, the various shapes, textures, and gestures he generates with it seem of a piece. Their braided output certainly contrasts and the musicians don’t seek bland consonance, instead engaging in a rapidly evolving give-and-take, sometimes holding on to a fertile sonic blend and sometimes disrupting the flow, as with any compelling duo improvisation. Below you can check out “Scudding,” where the divide between acoustic and electronic sounds is quite pronounced at times, but the interplay couldn’t be more fluid.

Recommended Shows in Berlin This Week

January 27: Frank Gratkowski, bass clarinet , clarinet, Joel Grip double bass, Jan Roder, double bass, and Harri Sjöström soprano & sopranino saxophones, 7:30 PM, Wolf & Galentz, Wollankstraße 112a, 13187 Berlin

January 27: Philipp Gropper’s Philm (Philipp Gropper, saxophone, Elias Stemeseder, piano, synthesizers, Robert Landfermann, double bass, and Leif Berger, drums); Lucy Zhao, pipa, 8 PM, 90mil, Holzmarktstrasse 19-23, 10243 Berlin

January 27: Earl Sweatshirt; Sideshow, 8 PM, Metropol, Nollendorfpl. 5, 10777 Berlin

January 28: Nicolas Collins, !trumpet & Birgit Ulher, trumpet, objects; Hanno Leichtmann, electronics, 8:30 PM, KM28, Karl Marx Straße 28, 12043 Berlin

January 28: Achim Kaufmann, piano, electronics, Yorgos Dimitriadis, drums, electronics, and Michael Thieke, clarinet, 8:30 PM, Sowieso, Weisestraße 24, 12049 Berlin

January 28: Camila Nebbia, tenor saxophone, and Robert Lucaciu, double bass; Olaf Rupp, guitar, 9 PM, Neue Zukunft, Alt-Stralau 68, 10245 Berlin

January 29: Tortoise, 8 PM, Haus des Rundfunks - Großer Sendesaal rbb, Masurenallee 8-14, 14057 Berlin

January 29: Nicholas Bussmann plays Ohnmacht-Trilogy Part 1: little ideas for voice and piano; Cottbusser Chor (Margareth Kammerer, Eduard Mont de Palol, Laura Mello, Yusuf Ergün, Aaron Snyder & Nicholas Bussmann), 8:30 PM, KM28, Karl Marx Straße 28, 12043 Berlin

January 30: Charlotte Hug, voice, viola, live Temporary-Son-Icons, and Lê Quan Ninh, percussion, 8: 30 PM, Exploratorium, Zossener Strasse 24, 10961, Berlin

January 30: Olga Reznichenko, piano, Michaël Attias, alto saxophone, Felix Henkelhausen, double bass, and Marius Wankel, drums, 8:30 PM, Donau115, Donaustraße 115, 12043 Berlin

January 30: New Schlippenbach Trio (Alexander von Schlippenbach, piano, Rudi Mahall, clarinet, bass clarinet, and Dag Magnus Narvesen, drums), 8:30 PM, Sowieso, Weisestraße 24, 12049 Berlin

January 31: Hilary Jeffery, brass, Eleni Poulou, synthesizer, Eric Thielemans, drums, and Aya Metwalli, voice; Christof Kurzmann, lloopp, and Marta Warelis, piano, 8:30 PM, Kühlspot Social Club, Lehderstrasse 74-79, 13086 Berlin

February 1: Cloud and Stone (Taiko Saito, vibraphone, Alexander Beierbach, tenor saxophone, and Maike Hilbig, double bass, 3:30 PM, Industriesalon Schöneweide, Reinbeckstraße 10, 12459 Berlin

February 1: George Xylouris, lute, voice, 9 PM, Urban Spree, Revaler Straße 99, 10245 Berlin

February 1: Dan Peter Sundland’s Home Stretch (Philipp Gropper, saxophone, Antonis Anissegos, piano, Dan Peter Sundland, bass guitar, and, Steve Heather, drums), 10 PM, B-Flat, Dircksenstr. 40, 10178 Berlin

February 2: Bill Frisell Trio (Bill Frisell, guitar, Luke Bergman, bass, and Rudy Royston, drums), 6:30 PM, Zig-Zag Jazz Club, Hauptstraße 89, 12159 Berlin

Febuary 2: Simon Rose, saxophone, Matthias Müller, trombone , and Michael Griener, drums, 8:30 PM, Kühlspot Social Club, Lehderstrasse 74-79, 13086 Berlin

Wow, that new Tortoise track is so vibrant. TFS!