Remembering New York jazz, now and then and now

Sexmob, Michael Blake, Sam Bardfeld, Jazz Doctors, Lesley Mok

Sexmob never went away, but it’s back nonetheless

With so much focus on what’s next, the music industry frequently leaves lots of good stuff in the dust, even in the world of jazz and improvised music. I thought about that tendency in relation to a clutch of new records by New York musicians who’ve kind of aged out of media attention for reasons that have nothing to do with quality. The three albums I’m about to discuss—all created by a crew of musicians who have been working together in various contexts and in one another’s orbit going back to the late 1990s—are all strong even if they don’t represent some new trend nor reinforce some rigid tradition.

The album that got me thinking about this topic is The Hard Way (Corbett vs. Dempsey), the first new recording by Sexmob in seven years, although the group’s previous album, Cultural Capital (Rex), was so off-the-radar it’s actually been a decade since the quartet dropped something that made much of a splash. Its members continue to work regularly, with slide trumpeter Steven Bernstein devoting much of his attention to his long-running Millennial Territory Orchestra, dropping four albums in the last couple of years, but it was still surprising to hear this old combo resurface. When the band first emerged in 1998 with the album Din of Inequity, co-produced by Bernstein with Scotty Hard (née Harding), its brash, ensemble-oriented attack was utterly refreshing, bringing an almost clichéd New York attitude and rock oomph to a sprawling array of post-bop modalities. In some ways the band helped pave the way for the success of a group like the Bad Plus, which soon embraced that jacked-up production for its own piano-based repertoire.

Fueled by the funky, hard-hitting grooves of bassist Tony Scherr and drummer Kenny Wollesen, with the extroverted squalls of alto saxophonist Briggan Krauss complementing Bernstein’s full-throated sound, Sexmob were one in a long-line of group’s laughing in response to the idea that jazz was dead. Over the next 15 years they engaged in a series of concept and/or composer-driven projects, such as essaying various James Bond themes or Nina Rota scores. It’d been a long time since I had checked out the group’s music, but prompted by the new album I’ve been pleasantly surprised how vital the quartet remains, with a sense of irreverent fun that’s long been Bernstein’s calling card.

As its title suggests, the new album underlines the pervasive role producer Hard(ing) has brought to the endeavor. He wrote and arranged all but one of the ten tracks with Bernstein, and his sonic thumbprints have never been heavier on a Sexmob record, laying down synthetic bass accents and giving the quartet a rock-ish energy, with heavy doses of dub, noise, and electronic influences bleeding into the din. Although every track features its fair share of improvisation, the band utterly eschews any post-bop orthodoxy where a simple theme is endlessly adorned with strings of lengthy solos. Instead, each solo feels more like an integral part of the composition, with others perpetually chiming in with answers and accents. The album opens with a tune called “Fletcher Henderson,” but it pretty much ignores that bandleader’s sonic legacy, instead embracing a slow, insinuating groove that opens up and tightens, with bits of horns untangling along the way. It concludes magnificently, with a solo passage by Krauss making his alto mimic the sound of someone sucking the last vestiges of a Slurpee through a long straw. You can check it out below.

Elsewhere the production often transforms the timbre of the brass, with the horns sounding brittle and metallic on a tune like “King Tang,” punching through the grinding grooves. Old pal John Medeski adds a characteristically fat-toned Hammond solo on “Banacek,” which suggests a vintage Blaxploitation theme colliding with a wall of blown-out amplification. “Lawn Mower” rides a ferocious bass riff, with blues guitar licks injected—not sure by who, as Krauss and Scherr are both credited on the instrument—and horns pushed way into the red in a way that obliterates any clear “jazz” feel. Guest pianistVijay Iyer offers some spare chordal interjections on “You Can Take a Myth,” a dub-drenched assortment of fits-and-starts, where Harding’s fader riding is the tune’s primary action. Still, as much as Harding gets the spotlight, that focus never comes at the expense of Sexmob as a crack band that seems to be having as much fun as ever.

Michael Blake reinvents himself again

Reedist Michael Blake is another great player I associate with the same era, location, and vibe, although he’s absolutely mild-mannered compared with Sexmob. His old group Slowpoke shared the rhythm section with Sexmob, and Bernstein has regularly appeared on his recordings, such as the 2008 album Hellbent and more recently on Blake’s 2022 brass-focused album Combobulate (Newvelle). While the trumpeter has tended to stick with a handful of projects over the long haul, the former has regularly formed and shut down new bands. In fact, only a handful of his ensembles have cut more than one recording. But Blake has never struck me as a dilettante so much as a deeply curious listener who’s gotten caught up in certain sounds and has regularly decided to dive in. He never tries to appropriate this sound or that, but instead he allows himself to see what he can do with a given tradition or style.

This past Friday he dropped Dance of the Mystic Bliss (P&M), the debut album from his new group Chroma Nova, with music born out of pandemic isolation. Blake also has a long history with Harding, who mixed this record. Several interesting threads come together on the recording, with Blake leading a group with four string players: guitarist Guilherme Monteiro, violinist Skye Steel, cellist Christopher Hoffman, and bassist Michael Bates. The band also includes three native Brazilians, with Monteiro joined by percussionists Rogerio Boccato and Mauro Refosco. Yet neither of those threads predominate because Blake doesn’t think along such narrow strictures. The opening track “Merle the Pearl” does showcase the blended strings, with sleek unison riffing that comes together and apart with the leader’s tenor, and it’s one of several tunes that borrow some of the galloping grooves of forro music, the Brazilian genre of choice here rather than usual samba or bossa nova. Parsing such components misses the point, as most of the compositions are multi-partite marvels that make big transitions with utter seamlessness. “La Couer Du Gardin” opens with Blake blowing tendrils of jaunty soprano over delicate guitar arpeggios, building in depth when the strings unfurl tender counterpoint to the sax melody, when suddenly Hoffman delivers an elliptic, sorrowful solo over a restrained mix of hard percussion and marimba. More Nordeste rhythms clop beneath the seductive “Little Demons,” with Blake unleashing his classic tenor attack over an irresistible bassline from Bates, only to shift into a bluesy guitar solo more redolent of New Orleans than Recife. You can listen below.

I don’t like everything on the record. The fuzzed-out guitar on “Topanga Burns” and the percussive breakdown captures the band at its most overwrought, with a slight jam band edge despite the airiness that permeates much of the arrangements, but that feels like a minor quibble. On several other pieces like “Prune Pluck Pangloss” and “The Meadow” Blake demonstrates fluency on the flute, an instrument he hasn’t played publicly before, and in general he’s been one of my favorite soprano saxophonist for decades, tempering the dryness of Steve Lacy without getting mawkish. Many of the tracks were written in response to the death of Blake’s mother Merle, with several reflecting her interest in gardening like “Weeds,” an appropriately multivalent excursion at once lyric and sorrowful with an unexpected closing part where the leader opens up on tenor, offering a lush, lyric beauty that’s always been characteristic of his best playing. His music has never been composed and assembled with such breadth and emotional range, and while Blake is years beyond the whippersnapper playing second fiddle to John Lurie in the later versions of the Lounge Lizards, I’d say he sounds as good or better than ever.

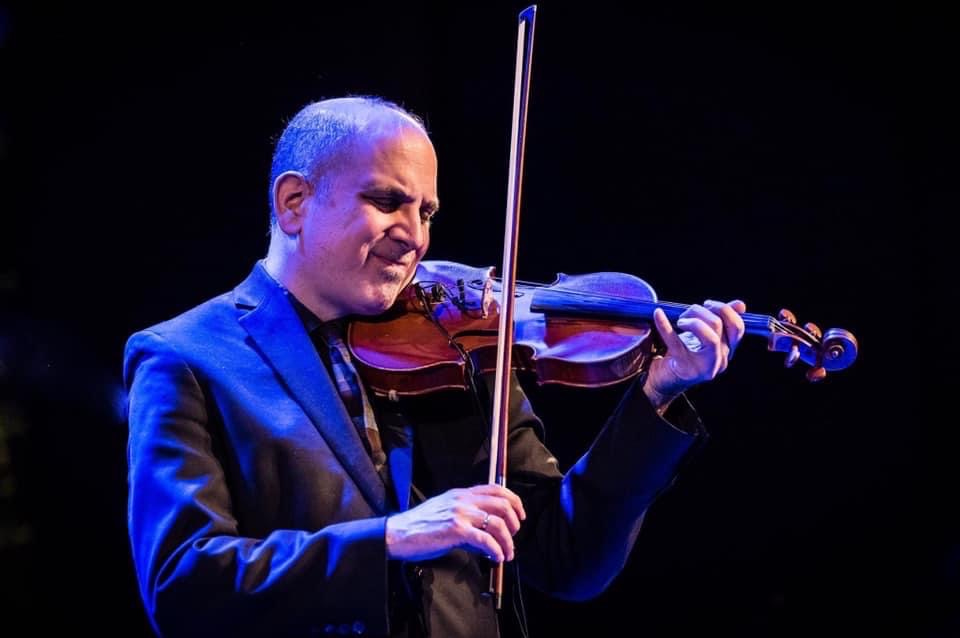

Sam Bardfeld’s old-school tone in the present

Violinist Sam Bardfeld cites Bernstein in the liner note essay he penned for his recent album Refuge (Brooklyn Jazz Underground), noting that the trumpeter once said, “We’re all weird,” explaining the essential outsider status of artists. The quote comes amid a discussion of how they’re all connected “a heart of darkness and to a spirit of iconoclastic individualism in the early American experience,” the refuge of the title. Bardfeld explored similar ideas on his 2017 trio album The Great Enthusiasms, made with pianist Kris Davis and drummer Michael Sarin. Sarin is back with the trio on the new record, while the excellent Jacob Sacks fills the piano chair.

Bardfeld is a sublimely versatile player, with tastes as broad as the folks I’ve already discussed here. In addition to a chunk of original pieces, the trio tackles the Andrew Hill title track, the opening tune on the pianist’s classic 1965 album Point of Departure, as well a song by his one-time employer Bruce Springsteen, “Atlantic City.” On the latter the trio digs deep into that song’s inherent darkness, embracing a kind of slightly out-of-sync rhythmic feel and freeness that elevates the ambiguity. But one needn’t look past his own tunes to appreciate his art, where he deftly bridges eras and styles with an off-kilter swing and slashing phrases voiced with an appealingly bracing tone. In fact, there’s something in his playing that reminds me of both Leroy Jenkins and Billy Bang, as there’s a graininess and a bite to his sound. The album opens with the delightfully lurching “Kick Me,” with an attractively bumpy swing feel by Sarin and hushed chords from Sacks, which give the violinist plenty of space and propulsion.

There’s a nicely jagged feel to “A Ribbon of Sooty Thought,” tumbling through a post-bop arrangement spiked with some old-school Stuff Smith-style swing, as piano and violin see-saw before Sacks sculpts a typical array of simmering harmonies beneath Bardfeld’s probing solo. Sacks pushes things out when he steps with a solo, leaning hard into left-handed interjections that recall early Cecil Taylor—check it out below.

“On the Seat of Which” serves up a much different groove, a kind of sideways funk that inspires a different attack from the violinist before they all coalesce around a cymbal-driven pointillism, only for the original rhythm to return. There’s even a touch of “new music” in “That Greeny Flower,” with a wide open coloristic exploration as the leader plays a bit with bow pressure and pizzicato. These days it feels like most improvising violinists have embraced a more experimental attack marked by scratch tones, unusual tuning schemes, and thick double stops, so it’s kind of a welcome respite to hear a more classic conception.

The Jazz Doctors will now see you

The Jazz Doctors will now see you

I’ve been pleasantly surprised by and a little shocked at the fact that I knew nothing about a 1984 album by a quartet called the Jazz Doctors until very recently. The band, which was really the Billy Bang Quartet, cut an album called Intensive Care for the Cadillac label, a British imprint, I would learn much later, that had previously issued key works by the likes of Johnny Dyani and a very young David Murray. The first Bang record I ever bought was a used copy of his 1979 album Sweet Space (Anima), an incredible record by a stunning band that included Lowe on tenor saxophone, along with drummer Steve McCall, alto saxophonist Luther Thomas, pianist Curtis Clark (who reportedly died last week, at age 73), bassist Wilber Morris, and his brother Lawrence “Butch” Morris, when he was still playing cornet. Anyway, the Jazz Doctors recall that sonic milieu, when the loft scene cats were starting to assess tradition through the lens of free jazz. Intensive Care was cut in London in 1983—at a studio owned by bassist and one-time Lennie Tristano associate Peter Ind—with Bang playing in a quartet with Lowe, bassist Rafael Garrett, and drummer Denis Charles (whose first name is still misspelled on the cover art with two “n’s.”).

The revived Cadillac imprint has just reissued the music on vinyl, but also on CD and digital where the recording is appended by music from a studio session from the following year—none of that had ever been released—although some of that second session has been lost. For the second session the rhythm section had changed, with bassist Wilber Morris and drummer Thurman Barker stepping in. According to the reissue’s press release “allegedly the changes had followed an altercation between Bang and Charles on the bandstand at a Wuppertal gig on the 25th October 1983.” I can only imagine the circumstances of the recordings, done in the middle of UK tours, were less than ideal, and the fact that both dates feature as many jazz standards as original tunes suggests these weren’t groups with a large repertoire of their own.

Listening to this stuff in conjunction with the recent Sam Bardfeld album struck a chord. He and Bang both play with distinctive voices, but their general tonal approach seems absent today. Bang’s improvising is simultaneously raw and lyric, and his rapport with Lowe is stunning. While each of the two rhythm sections are elastic, deftly fluent in swing and free settings, the playing blurs any lines between those two approaches. The first album features a sublime account of one of Butch Morris’s best tunes, “Spooning”—check it out below—which is nearly as perfect as the Jackie McLean classic “Little Melonae” that opens the album. The record, which contains one strong tune apiece from Bang and Lowe, concludes with a roiling take on Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman,” where the violinist is a true dervish, slashing away at his instrument with astonishing rhythmic intensity.

It’s a shame that four original tunes from the second session have been lost, but since I didn’t even know about the first album until recently, I can’t complain about hearing Bang and Lowe take on Monk’s “I Mean You,” the Sonny Rollins standard “Pent Up House,” and Coltrane’s “Mr. Syms,” in addition to a two-part Bang composition called “Suite for Gamma.” I don’t know if the looseness here is standard for the era, or if such recordings captured groups that hadn’t rehearsed enough, but either way the vibe is amazing. I wish we could experience more music making that felt this natural and chill, with a devotion to nailing it without an obsession about how exacting the execution was. This stuff says way more than mere perfection could ever transmit. Definitely the best archival thing I’ve encountered so far this year.

Catching up with Lesley Mok, on record and in Berlin

I first began seeing Lesley Mok’s name a couple of years ago, but it’s only this year that I’ve actually been able to hear her music. Back in April I caught an amazing set with her from Anna Webber’s new quintet Shimmer Wince while on a trip back to Chicago, and I’ve subsequently spent a lot of time listening to her impressive debut album The Living Collection (American Dreams), where she leads a superb 10-piece ensemble. The nine-part suite—each section of which is titled by parts of a poem by Jorie Graham called “Scarcely There”—is concerned with different sorts of breath, from the first inhalation we take after birth to the notion of a group breathing together as an organizing principle. Mok embraces various meanings and uses for breath in a compositional context, and the idea never weighs too heavily on the sounds her remarkable ensemble produces together.

Mok’s writing seems quite open and this music wouldn’t succeed without such a cast of top-flight players. The recording was beautifully engineered by Weston Olencki, bringing out an impressive tactility and richness in the group sound, while also providing electronic squiggles that remind me of Ikue Mori’s work. The arrangements guide players in and out of situations with impressive fluidity, with a primary focus on timbre and interplay, although the way some of the horns emerge from Corey Smythe’s tender explorations on the opening piece “It wants,” makes clear that Mok is also thinking about harmony. Each piece unfurls patiently, with ever-changing sonic blends, as different groupings perpetually coalesce and pull apart to forge new alliances. On “its furious pace,” which you can hear below, Mok shapes a kind of loose sonic armature of delicate cymbal patter and sudden percussion surges. Long tones played by trumpeter Adam O’Farrill and trombonist Kalan Leung support conversational tangles between cellist Aliya Ultan and violist Joanna Mattrey, as well as the weightless winds of David Leon and Yuma Uesaka. Many of the pieces feel adrift at first listen, but there is clearly a sense of design that allows patterns to emerge incrementally.

Mok eschews typical narrative structures, even when certain passages evoke a more traditional approach. Solos weave in and out of mewling constructions that can turn themselves inside out like some kind of sonic Möbius strip, constantly shifting the focal point in ways that make us wonder if we heard things correctly from the start. The music is insanely malleable, and I’m really curious to hear how this work plays out over time with repeated performances, as there’s so many ideas knitted within these structures. It seems certain it would never sound the same twice.

Mok is in Berlin on Saturday night, co-leading a show at Donau115 on Saturday, June 3, with bassist Florian Herzog, a regular collaborator who also plays on The Living Collection. The rest of the ensemble includes vocalist Cansu Tanrikulu, saxophonist Camila Nebbia, and pianist Julius Windisch.

Recommended concerts in Berlin this week

May 31: Harmonic Space Prime Time #3 with solo performances by Judith Hamann (cello) and Sarah Saviet (violin), and a group piece led by Weston Olencki, 8 PM, KM 28, Karl-Marx-Straße 28, 12043 Berlin

June 1: Xavier Lopez; Nandita Kumar; Lucio Capece, 8 PM, Petersburg Art Space,

Kaiserin-Augusta-Allee 101, 10553 Berlin (Aufgang II, 1 OG)

June 2: Jyoti Thakar (sitar) and Arvind Paranjape (tabla), 8 PM, KM28, Karl-Marx-Straße 28, 12043 Berlin

June 3: Myra Melford leads trios with Zeena Parkins (harp) & Miya Masaoka (koto) and Michael Formanek (bass) & Ches Smith (drums), 7 PM, Pierre Boulez Saal, Französische Straße 33D, 10117 Berlin

June 4: Sessa, DJ Falco Teichmann, 8:30 PM, Kantine am Berghain, 70 Am Wriezener Bahnhof, 10243 Berlin