My favorite albums of 2022, part two

Unranked, because what is the best?

Thanks to everyone for checking out the first Nowhere Street dispatch, especially those who subscribed. Today I’m sharing the rest of an unranked list of my forty favorite albums of 2022—at least at the time I made the list. Next week I’ll get into a new format of reviews and previews that will be a primary feature moving forward.

In the meantime you might want to check out the latest installment of the best contemporary music column I have the privilege of writing at Bandcamp Daily, which was published yesterday.

Now on to 20 more albums that brought me pleasure, nourishment, and stimulation in 2022. You can check out the first 20 here.

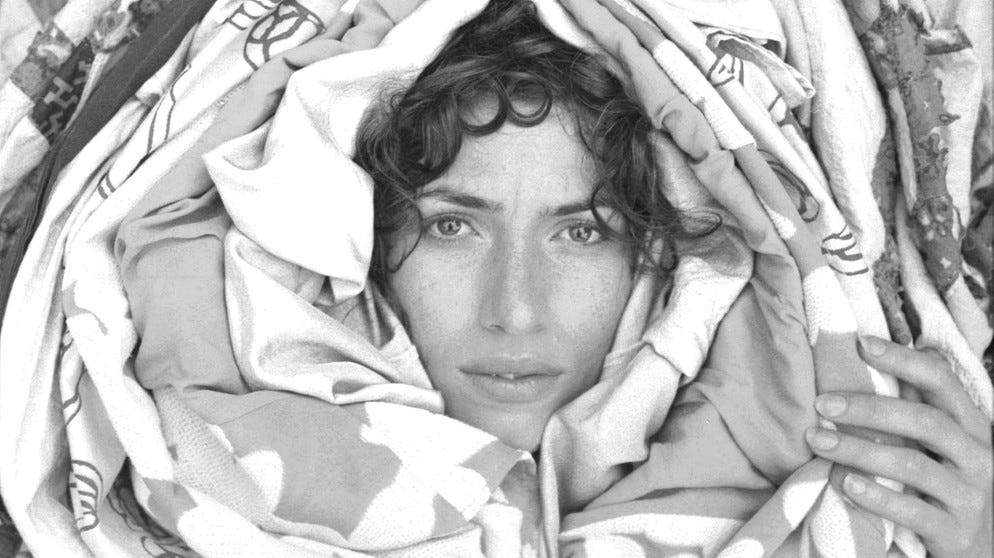

Aldous Harding, Warm Chris (4AD)

I was thrown for an early loop by the restraint if not simplicity of the latest by Aldous Harding, but that’s because I didn’t listen closely enough. The songs are extraordinary both in construction and melody, and there’s plenty going on. But what really sealed the deal beyond this growth was how she has grown as a singer. She inhabits each little word, changing her persona and voice quality that makes an already diverse batch of songs seem even more powerful. Whether the close-miked perfection of the title track or the harrowing closer, where Harding unleashes three entirely different vocal characters, it’s a genuine classic. She’s at the point in her career where less authoritative artists might dumb it down, Harding is running the other way and making better and better work.

Rob Mazurek Quartet, Father’s Wing (Rogue Art)

In a period marked by artistic retrenchment, cornetist, composer, and bandleader Rob Mazurek slowed his output in recent years, but the recordings he’s shared represent some of the most powerful, focused music in his fruitful career. This quartet with pianist Kris Davis, bassist Ingebrigt Håker Flaten, and drummer Chad Taylor has become crazy good, and this collection made as an homage to his late father, who passed away in 2016, and it consolidates the leader’s strengths in a new way: his primal vocal howls, electronic textures, and, of course, his protean, lyric blowing melding convincingly and concisely. Of course, the band is unstoppable. Where hear Davis thrive, whether elliptic or in her improvising or gushing sound, Håker Flaten a propulsion machine with unerring structural thinking, and the redoubtable Taylor, who has been driving many of the greatest bands or four time—I could listen to his snare rim work all day long.

Dewa Alit & Gamelan Salukat, Chasing the Phantom (Black Truffle)

Gamelan music feels ancient, but there have always been composers pushing the tradition forward even though we rarely get to experience the newer sounds in the west. That makes the emergence of Dewa Alit’s work even more valuable. I loved the first collection of music from the Balinese composer released on Black Truffle a couple of years ago, but these two new pieces are something else, staggering in their precision and originality. Alit’s ability to imagine new possibilities for gamelan, often suggestion electronic music, are staggering.

Helga Myhr, Andsyning (Heilo)

Hardanger fiddle player Helga Myrh was one of numerous musicians I discovered this past year thanks to their association with Motvind, the dazzling Norwegian label and festival that’s responsible for a lot of exciting sounds these days. Myrh released a gorgeous solo album for the imprint, but this new ensemble recording offers a much richer portrait of her vision. Grounded by an elastic rhythm section featuring bassist Adrian Fiskum Myrh and drummer Michaela Antalová, while she’s flanked by violinist Rasmus Kjorstad (who also adds the Norwegian zither called the langeleik and jaw harp). The ensemble is rounded by the remarkable folk singer Malin Alander, with whom Myrh harmonizes to stunning effect. The music may be rooted in Norwegian folk tradition, but the quintet swings and stretches like a jazz group, with each instrumentalist deploying heady extended techniques at time. One of the most stunning, expansive listening experiences of the year, and another reminder of the endlessly renewable forms, modes, and ideas embedded in traditional music.

Lucrecia Dalt, ¡Ay! (RVNG Intl)

I’m still not sure if I’ve enjoyed this album so much because Lucrecia Dalt’s embrace of South American roots seemed unexpected or if it’s due to her songwriting and skilled production melding with live instrumentation—especially double bassist Nick Dunston, who supports most of the record with his warm, woody lines, but also trumpeter Lina Allemano and winds player Edith Steyer—but each time I checked back in to see if the novelty had worn off, I ended up digging it more. It all feels easygoing, sensually humid, and rich, with Dalt’s voice occupying the tunes with an abiding grace and sense of comfort. There’s a clear sense of nostalgia at work, but the modern flourishes never really feel like a glib collision; it’s considered, but utterly natural. I keep hearing this in tandem with Jockstrap’s 2022 album I Love You Jennifer B (Warp)—which I dig despite its abundant flaws. Whereas Georgia Ellery too often cedes her stunning voice and songwriting to the heavy-handed club production of her musical partner Taylor Skye, Dalt keeps the balance right.

Maya Bennardo, Four Strings (Kuyin)

Violinist Maya Bennardo—a member of Mivos Quartet and half of the string duo andPlay—has demonstrated prodigious technique and stylistic versatility in those projects, but on this sublime solo album she shares a more experimental side of her craft, tackling two minimalist gems from Wandelweiser Collective mainstay Eva-Maria Houben and the young Swedish composer Kristofer Svensson. Houben’s title work, for open strings, moves in slow motion as extended long tones are interrupted by brittle frictive grain and silence. Svensson’s “Duk med broderi och bordets kant” explores similar terrain while enfolding a sporadically recurring motif and arching phrases that seem plucked from Swedish folk tradition or swiped from baroque music and played at quarter-speed. Either way, this was one the most comforting albums of 2022, a stunning exercise in stillness.

J.D. Allen, Americana Vol. II (Savant)

I’m not sure what it means that saxophonist JD Allen has reunited with his long-time rhythm section of bassist Gregg August and drummer Rudy Royston on this sorta sequel of tunes conveying some sense of the titular subject, but I couldn’t be happier to hear them together again. That’s no shine on bassist Ian Kenselaar and drummer Nic Cacioppo, the superb rhythm section that worked on Allen’s last few trio recordings, but these older cats run deep, which helps on a record rooted in blues and folk material. They’re joined by guitarist Charlie Hunter throughout, a far more direct and earthy player than Liberty Ellman, who made a couple of albums with the trio, who pulls more of a heavy blues vibe from the group.

Bill Nace, Through a Room (Drag City)

Sculpting crude sounds with more finesse, control, and imagination than ever, Bill Nace delivered one of my favorite psychedelic excursions with this 3-D trip crafted with Cooper Crain. The tones—produced primarily with his old laptop guitar, but also with some hurdy-gurdy, tapes, objects, and his recent tool of choice, a Japanese taishōgoto—remain as curdled and nasty as ever, but the meticulous layering, the emergence of almost serene swells, and the ultra-sharp sense of dynamics and scale reduce any grime to means to a glorious end. Sometimes I feel like I’m hearing the music from underwater and sometimes it seems like there’s a little boomboxes rattling around inside my ears, and I love both experiences.

No Hay Banda, I had a dream about this place (No Hay Discos)

I can’t help but admire a group that goes all in, and Montreal’s No Hay Banda, key figures in the city’s new music scene since forming in 2016, commit big time on this knockout double CD. All four pieces—works by Anthony Tan, Sabrina Schroeder, Andrea Young, and Mauricio Pauly—are all unabashedly abstract, but the music is riveting in its power and the ensemble’s devotion to slow development is dazzling.

Lisa Ullén-Elsa Bergman-Anna Lund, Space (Relative Pitch)

2022 was the year I really started grasping that there’s something very deep going on in Stockholm, Sweden, where a new breed of improvisers equally fluent and interested in contemporary and experimental music are making some crazy shit happen. Sadly, the local citizenry doesn’t seem interested. Among the heaviest hitters is veteran pianist Lisa Ullén. As with her bandmates, bassist Elsa Bergman and drummer Anna Lund, I took notice of them all when they were working in Anna Högberg’s Attack! But they’ve all got their own things brewing, and this improvising trio has taken the music in a much more brooding, ruminative direction that’s no less visceral. I heard them live in November and their rapport and ease has grown precipitously.

John Luther Adams, Sila: the Breath of the World (Cantaloupe)

I experience a performance of Sila: the Breath of the World—the second grand outdoor work by John Luther Adams following his percussion epic Inuksuit, on the campus of Northwestern University in Evanston in 2015. The performance was organized by percussionist Doug Perkins, who has worked closely with the composer in making this impossible scores work, and Perkins helped realize this magnificent recording played a raft of folks at the University of Michigan along with the Crossing, the most versatile new music choir there is, and JACK Quartet. Part of the work’s grandeur is its spatialized effect, where the output of five different ensembles within the massed conductor-free orchestra combine in ever-shifting ways depending on where the listener is situated. In a live performance we’re in the middle of the action, and we can move around to alter our perspective, yet even with this fixed recording that music’s power still comes across clearly. The title is accurate. The music breathes in a very meditative, organic way, as if its sounds were coming directly from nature itself, and conjuring such enormity is no mean feat.

Horse Lords, Comradely Objects (RVNG Intl)

Now based in Berlin, the Horse Lords continue to shorten the distance between intellect and gut, deftly borrowing, executing, and reframing ideas of experimental music, whether just intonation or wild psychoacoustic effects with off-kilter funk. Guitarist Owen Gardner collides the sort of spindly hypnosis of Mauritanian music with taut repetitions of funk, bassist Max Eilbacher threads the whole stew with muscular grooves and squelchly electronics, drummer Sam Haberman spews polyrhythmic patterns in tricky time signatures, and saxophonist/percussionist Andrew Bernstein functions as the secret weapon, alchemically weaving it all together in something far more complex, rigorous, and thoughtful than the kind of polyglot mashups endlessly thrust upon us these days. Lots of people have ears as broad and interests as wide as these folks, but there aren’t many that honor the sources by going all the way and actually pulling it off.

Nancy Mounir, Nozhet El Nofous (Simsara)

I first heard about the work of Egypt’s Nancy Mounir a few years ago, and it made more sense on paper than in my ears, but with the full breadth of her unique vision on display I was knocked out. She transplants historical recordings of Arabic female singers made around a century ago within new arrangements that blend the atmosphere and surface noise of old 78 records in the present, with a sorrowful pop gloss. The results are gorgeous, and imaginatively update an ancient sound without compromising it, but part of her research is examining female artists who were shut out of the 1932 Congress of Arab Music in Cairo, which standardized Arabic tuning but crushed ideas and approaches outside of the chosen system. The female voices we hear on this album were shut out from participating. Mounir both makes a powerful feminist statement while highlighting some of the variety we lost in that homogenization process.

Gard Nilssen Acoustic Unity, Elastic Wave (ECM)

After seeing this trio with saxophonist André Roligheten and bassist Petter Eldh play this music several times in 2022 it’s only become clearer that drummer Gard Nilssen has one of the best working bands on the planet. Elastic, indeed. But that also means that this recording feels like a template or a starting point for what the group can do with the material. That doesn’t mean the music doesn’t hold up, but it doesn’t fully capture the gut punch of hearing them live.

Jeff Parker, Mondays at the Enfield Tennis Club (Eremite/Aguirre)

During his many years in Chicago guitarist Jeff Parker organized weekly sessions with a fixed band at a bar in Wicker Park called Rodan. They were groove-oriented improvisations with bassist Jason Ajemian and drummer Nori Tanaka, and later with bassist Joshua Abrams and Parker’s bandmate in Tortoise, drummer John Herndon. Now ensconced in Los Angeles, Parker has forged an even better weekly residence with the band featured on this astonishing document—bassist Anna Butterss, saxophonist/keyboardist Josh Johnson, and drummer Jay Bellerose. The music is intimate, humid, and expansive, with each of these four pieces extended to 25 minutes. I’d say this Parker’s favorite way to make music and his ardor for the context practically drips from the head-nodding rhythms. The guitarist also released an excellent trio session with drummer Nasheet Waits and bassist Eric Revis called Eastside Romp, but the organic vibe on display with the quartet is more enveloping and complete, with a palpable sense of community and camaraderie.

Oren Ambarchi, Shebang! (Drag City)

Guitarist Oren Ambarchi has utterly mastered a practice of music-making that assembles highly idiosyncratic players from around the globe in a seamless patchwork of episodes. He’s a conductor in the way he decides who to enlist, in what context, and how to fit it all together, and when a cast including Chris Abrahams, Jim O’Rourke, Julia Reidy, Sam Dunscombe, and BJ Cole, with an elastic, shape-shifting groove machine powered by Johan Berthling and Joe Talia, well, it more than lives up to the billing.

Oùat, Elastic Bricks (Umlaut)

In 2020 Matthew Shipp wrote a story about Black Mystery School pianists who belonged to a category of his own design for New Music USA. The points he made have resonated with me more and more over time, and this superb French-Swedish-German trio with pianist Simon Sieger, bassist Joel Grip, and drummer Michael Griener definitely fits into Shipp’s equation, at least in my mind. In December this same trio released its second album of 2022 with The Strange Adventures of Jesper Klimt, a fantastic end-to-end interpretation of the overlooked yet brilliant Swedish pianist and composer Per-Henrik Wallin’s mid-80s album Coyote, but I think I prefer their debut, flush with knotty, hooky tunes. mostly by Grip. The trio clearly adores a tradition of idiosyncratic pianists like Monk, Nichols, Hope, and Hasaan, but while the evoke it in their own music, they enjoy a more collective approach in its delivery. Every year or so we need some reminder of why jazz is so elusively brilliant, and Oùat did it for me this past year.

Bitchin Bajas, Bajascillators (Drag City)

Over several years of delicately etched refinement this Chicago trio reemerged with a new instrumental palette—in three of four cases augmented by delicate cymbal work from drummer Mike Reed, Nori Tanaka and their Cave cohort Rex McMurry—that somehow evokes and simultaneously eviscerates the chintzy digitalia of new age, Cooper Crain, Dan Quinlivan, and Rob Frye achieve the sort of chimerical sophistication and organic thematic propulsion of Terry Riley and Steve Reich. The trio’s focus is tightening, while its possibilities keep expanding.

Egil Kalman, Kingdom of Bells (Egil Kalman Plays the Synthi 100) (Ideal)

Sweden’s Egil Kalman is kind of an honorary Norwegian considering his presence and importance to the Motvind crew. He plays in the collective Miman with Hans Kjorstad and Andreas Røysum, he plays in the Marthe Lea Band, and he’s part of Völvur, the ad hoc group that collaborated with Alasdair Roberts on his superb 2021 album The Old Fabled River (Drag City). He’s primarily a double bassist, but he regularly pivots around to an analog synthesizer in performance, deftly complementing or contrasting his acoustic low-end with some infectiously squiggly. He’s an amazing resourceful musician. On this record he sticks exclusively to the Synthi 100, exploding any lines between post-Subotnick blorp, psychoacoustic drone, and Terry Riley hypnosis. If only the rising tide of analog synth records could be matched with such an increase in quality.